As this Wikipedia article states, “Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called the theory of knowledge, it examines what knowledge is and what types of knowledge there are. It further investigates the sources of knowledge, like perception, inference, and testimony, to determine how knowledge is created. Another topic is the extent and limits of knowledge, confronting questions about what people can and cannot know. Other central concepts include belief, truth, justification, evidence, and reason. Epistemology is one of the main branches of philosophy besides fields like ethics, logic, and metaphysics.”

As stated in an earlier post, “What Exists?”, “In his doctrine known as ‘Nothing but Mentality (Chinese: 心外無法),’ Buddha teaches that mentality is the only perduring reality in the cosmos. Furthermore, mentality exists in two distinct states: quiescent and fluctuating. These two states of quiescent and fluctuating mentality explain the entirety of existence in the cosmos.”

Therefore, in the Buddha’s three-body cosmos, in addition to the Buddha himself, there are two realms of mentality with different fluctuation states. The quiescent mentality belongs to the imperceivable Ultimate Reality, while the realm of the fluctuating mentality manifests as the visible, phenomenal world that humans can experience. Consequently, the Buddha teaches that humans require two means of knowledge to understand these two domains with different levels of visibility: inference to understand the visible phenomenal world, where mentality fluctuates, and direct perception to understand the invisible realm, where mentality is quiescent.

However, the current scope of epistemology not only treats inference as the sole means of human knowledge but also excludes direct perception as a potential option. Indeed, the concept of perceiving nature directly as a means of human knowledge does not even exist in the current scope of epistemology.

However, according to Buddha, the potential to perceive nature directly is within all humanity. Hopefully, our exploration of Buddhist epistemology can expand the current scope of epistemology to include direct perception, thus enabling humanity to understand both the visible and invisible phenomena.

The exploration of epistemology begins with an understanding of how humanity knows what it knows, through a highly informative dialogue between Dr. Menachem Fisch, an internationally renowned historian and philosopher of science, and Dr. Robert L. Kuhn, the host of Closer to Truth. Their contemporary language can significantly enhance our understanding of Buddha’s teachings from thousands of years ago.

“How do we know what we know?” is the question Dr. Robert L. Kuhn asked his guest to start the conversation.

Dr. Fisch started by stating that, according to “latter-day philosophy,” “we do not know by our eyes or by our ears, but by means of the words we speak.”

Instead, Dr. Fisch suggested that “we are stimulated by the world,” and while “the world impacts on us in a causal manner through all our senses, but the content imparted on those stimuli is the reading in of the mind. It’s imparted by the mind.”

Dr. Fisch continued, “How we know is by means of their conceptualization.” “Sitting in the command room of our minds with the inner-eyes and looking out, … we don’t look out the windows of our eyes; everything happens within the head,… so sitting back on that armchair in the command console, and seeing on the screen the world that we experience, all that data has already been fashioned and conceptualized by our minds in ways that we do not govern.” “This is sensing.”

“Knowing,” Dr. Fisch continued, “is to render explicit those conceptualizations. In other words, to take stock explicitly, um, that’s a horse, ah, I am talking to an interviewer, and so on and so forth.” “What we can know, not what we can feel, is the function of the language of conceptual schemes, the concepts by which we conceptualize.”

Additionally, Dr. Fisch suggested, “if you look into the dictionary, words are explained by other words. The conceptual scheme, the vocabulary at our disposal, by which we experience and by which we know, is inferentially connected.” “In other words, if this point is north of that, then that point is south of that. That is about the meaning of the words. This isn’t an empirical fact. This is about how these concepts relate to each other. The limits of what we can know, the limits of our world, is the limits of our language!”

“The intriguing thing about bringing language into epistemology is that you can only know something new by using old words. If you invent a new term, it’s just a tag, not a concept.” “Like every person in this studio, you are unique. But the only way I can account for your uniqueness is by means of a set of concepts by which you are likened to others.”

“We know by means of using a concept.” Using a concept is to liken what we see to something else. So, concepts are little metaphors, a little class names.”

Dr. Kuhn immediately recognized the immensity of Dr. Fisch’s words as he questioned, “What prevents you from cascading into skepticism where we can’t know anything? Everything is related to something else. I have no foundation between what I believe and what the world really is. So, how do I know anything?”

In response, Dr. Fisch asked Dr. Kuhn, “Define know.” However, he answered his own question before receiving an answer as he continued, “What you are saying now is that we should be skeptical about knowing for sure, about how things stand in themselves, not how things are experienced by us.”

“How things are experienced by us,” Dr. Fisch expounded, “is already language informed, or concept informed.” “We know pretty much about the self we experience, the world we experience, the world we find ourselves living in.” “We got it right. We got it right according to our standards, no other standards.”

“Do we know things stand in themselves?”

“God knows,” was the reply.

In Dr. Fisch’s opinion, with only inferentially connected vocabulary at our disposal, humans are seemingly cursed only to know “how things are experienced by us,” not “how things stand in themselves.“

Of course, it is not so with Buddhism. Although it is true that there is no God or any deity in Buddhism to reveal to humanity “how things stand in themselves,” there is our historical Shakyamuni Buddha, who, as a Tathagata and encompassing “all objects of knowledge” that nature offers, can teach humanity “things as they are,” as discussed in Post 3. Like all enlightened individuals, a Buddha’s knowledge of “things as they are” comes not from revelation nor inferential word-based knowledge, but from direct perception, a topic we will discuss in Post 25.

But first, we discuss inference, the other means of knowledge that Buddha teaches. The means of knowledge is known in Romanized Sanskrit as Pramana (Chinese: 量).

Inference (Romanized Sanskrit: anumana; Chinese: 比量), according to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, “allows us to glean knowledge concerning objects that are not directly evident to the senses.”

Anumana is closely associated with another concept known in Romanized Sanskrit as agamadharma (Chinese: 教法), which, according to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “in Sanskrit, ‘scriptural dharma.’ In contrast to adhigamadharma, it refers to the mere conceptual understanding of Buddha’s teachings through studying Buddhist sūtras.”

Let’s now try to understand the first means of knowledge in Buddhism: inference, which “allows us to glean knowledge concerning objects that are not directly evident to the senses.”

Obviously, inference refers to the inferentially connected nature of word-based knowledge.

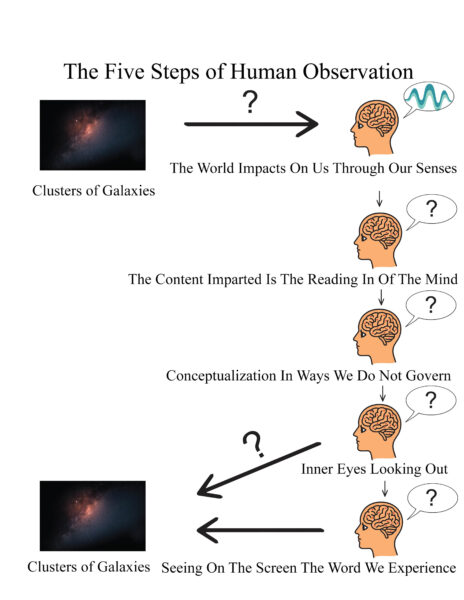

To understand what the “objects that are not directly evident to the senses” are, we turn to what Dr. Fisch describes as the following five steps of sensing.

- “the world impacts on us in a causal manner through all our senses,”

- “the content imparted on those stimuli is the reading-in of the mind,”

- “the content gets fashioned and conceptualized by our minds in ways that we do not govern,”

- “Sitting in the command room of our minds with the inner eyes and looking out,”

- “seeing on the screen the world that we experience.”

In the following discussion, we use observation as an example of sensing and a distant galaxy as the object of observation, as shown in the above image.

As the descriptions indicate and the image above shows, the “only objects that are not directly evident to the senses” are the distant galaxy clusters. All others are “directly” evident to the eyes or the brain, which are the senses. So, inference refers to the inferentially connected word-based knowledge humanity uses to understand “the world we experience.”

With that understanding, we can comprehend why “scriptural dharma refers to the mere conceptual understanding of Buddha’s teachings through studying Buddhist sūtras.” It is because what one learns from word-based knowledge is already “conceptualized in ways we do not govern.“

As can be seen from the image above, the observation process starts with the “content” of the galaxy impacting the eyes, becomes the “reading in” of the mind,” where it is conceptualized “in ways we do not govern,” and then through “the command room of our minds with the inner eyes looking out,” the “world we experience” becomes can be “seen.”

However, as also shown in the image, many details are left out, and assumptions are made. For example, how does the “content” of the galaxy get sensed by the eyes without crashing into them? What carries the “content” from the galaxy to the eyes to be sensed to become the “reading in of the mind?” What happens to the “content” after becoming “reading in of the mind? Are there really a “command room” or “inner eyes looking out” in the brain? Or are these just assumptions to cover what humans do not understand? Most importantly, what is “conceptualization in ways we do not govern” that turns the invisible “content” of the first step into becoming “the world we experience” that can be “seen” in the last step?”

The fact is that these are questions that even a highly educated and knowledgeable scholar who relies on inferentially connected word-based knowledge to understand the world cannot be expected to comprehend.

To the extent that inferentially connected word-based knowledge cannot inform “how things stand in themselves,” no one using it can answer “What Exists?” When one cannot answer “What Exists?’ one cannot be expected to know that all five steps of sensing involve consciousness.

This is what Buddha teaches in his doctrine known as the Five Aggregates. The Five Aggregates are Buddha’s teaching on the five steps of sensing that correspond precisely to the five steps Dr. Fisch describes, except that consciousness is incorporated into each step. If you wish to know how consciousness is involved and what “conceptualization in ways we do not govern” does in the five steps of sensing, please visit Post 27.

Indeed, the significance of the five sensing steps is that they turn the invisible “content” from the first step into “the world we experience” that can be “seen” in the last step. What makes it possible is the third step of the process: “conceptualization in ways we do not govern.“

This is the meaning of Dr. Fisch’s opening statement, “according to latter-day philosophy, we do not know by our eyes or by our ears.” Indeed, when one looks out the window and sees a beautiful world, how many of them know that they are manifesting it instead of learning it because of “conceptualization in ways we do not govern?” There would be none. It is because “conceptualization” happens “in ways they do not govern,” i.e., without anyone knowing or controlling it. Indeed, outside of Buddha’s Five Aggregates, no one else can tell humanity the details of “conceptualization in ways we do not govern.”

It is also the meaning of quantum mechanics that “suggests that reality at its fundamental level is uncertain, fluid, and dependent on observation.” However, while this suggestion is correct, it is only a suggestion to explain quantum mechanics, one that not all quantum scientists have faith in.

It is also what the three enlightened people in the Verification Category tell us: when the mind becomes quiescent, observation stops. When observation stops, the universe disappears simultaneously, verifying what Buddha teaches in the Diamond Sūtra.

“All conditioned phenomena are like the illusions of dreams or shadows of bubbles (Chinese: 一切有為法, 如夢幻泡影),

Like dew or lightning, this is how to view them correctly.” (Chinese: 如露亦如電).”

As discussed in Post 8, Buddha holds that the self-nature of our universe is “imaginary” and “dependent.” The self-nature of the universe is “imaginary” and “dependent” because it is conceptualized in the mind and dependent on observation to manifest.

Before we discuss direct perception, in the next post, we discuss the Kalama Sūtra, in which the Buddha offers his opinion on the use of word-based knowledge in the search for an unchanging Truth.

(If you like this post, please like it on our Facebook page and share. Thank you.)