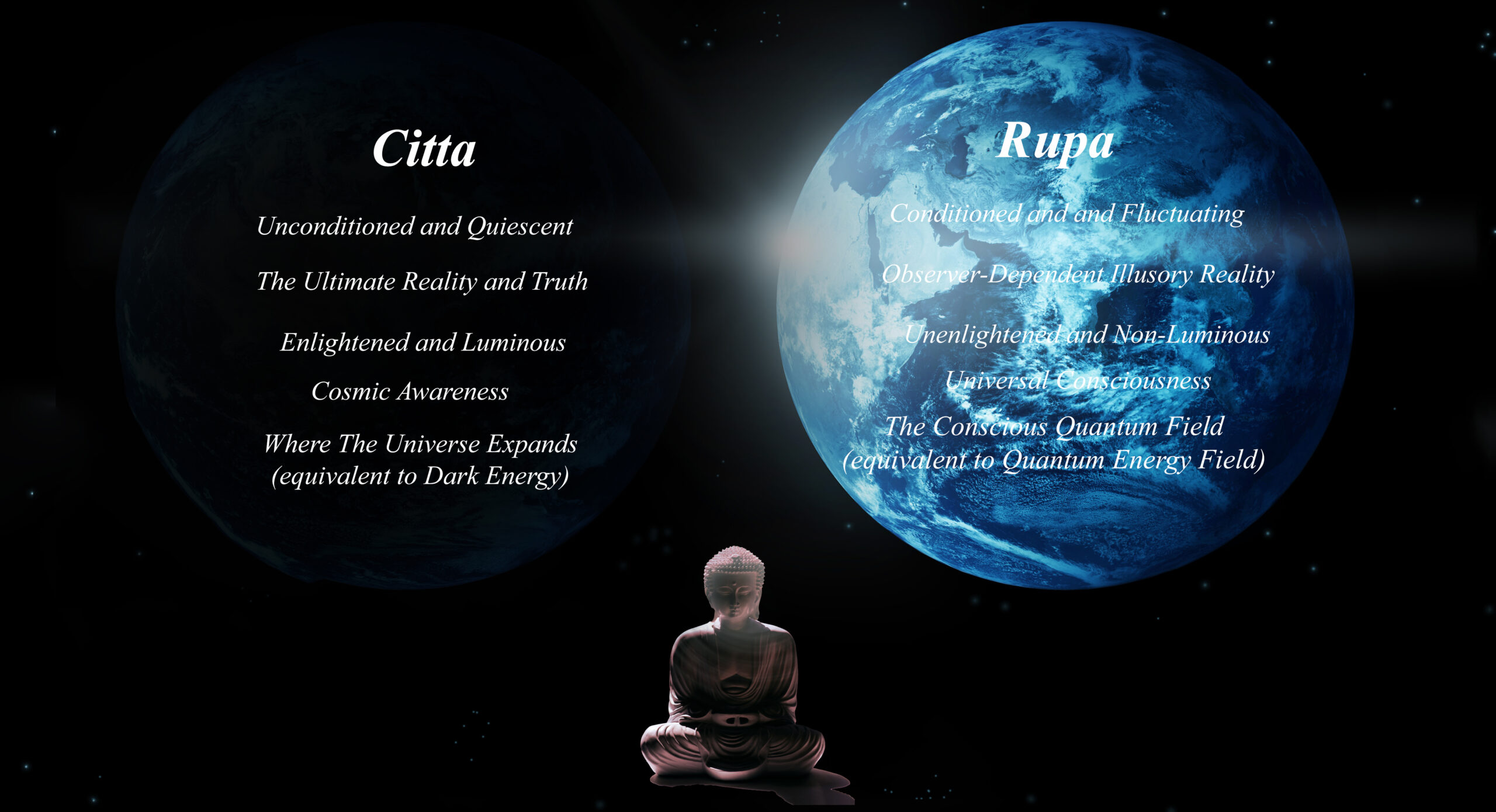

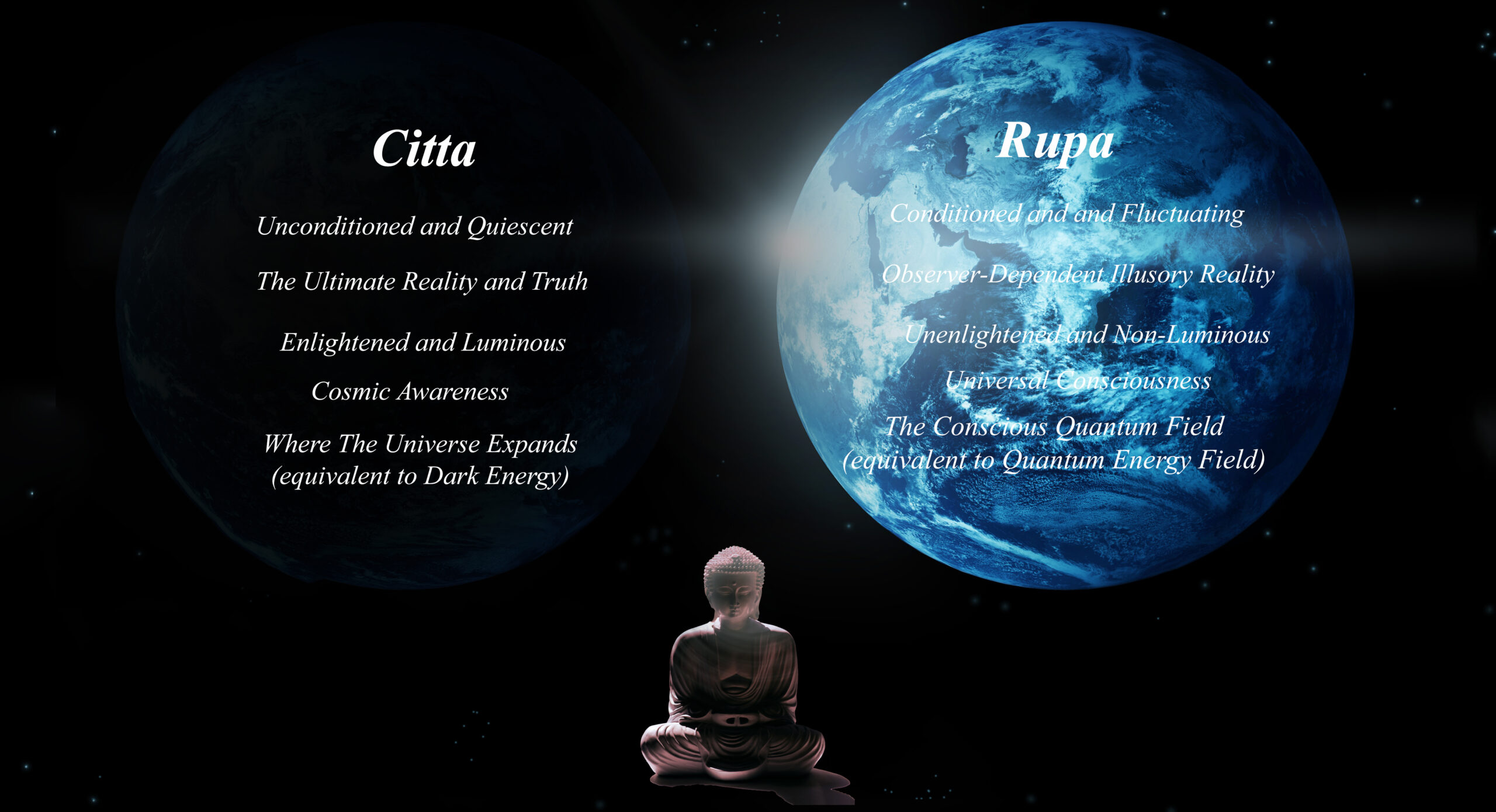

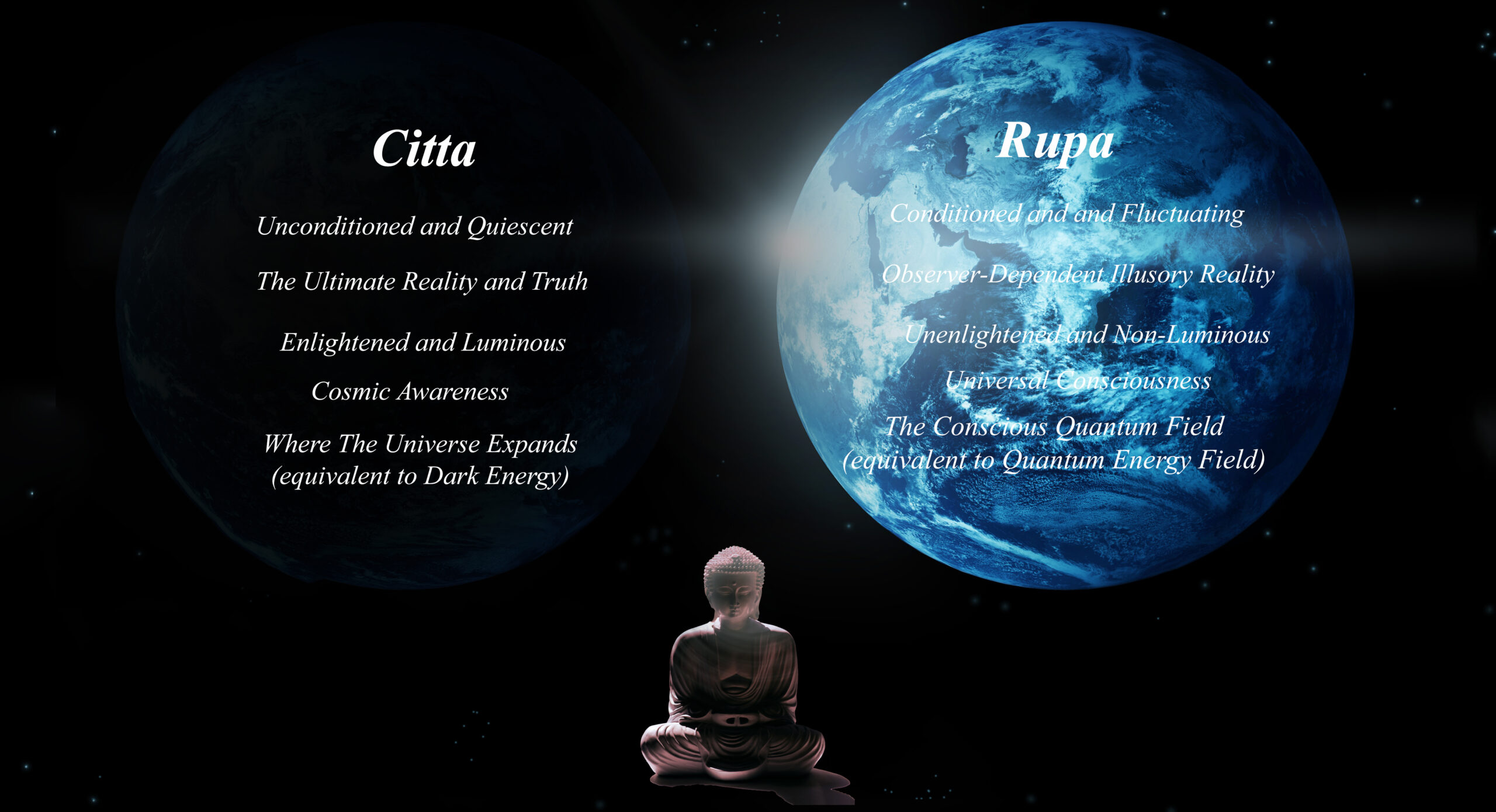

In this post, we discuss the Four Realms of Reality, a Buddhist doctrine in which the Buddha teaches that there are four ways of understanding reality between Citta and Rupa, the two realms of reality that comprise the Buddha’s three-body cosmos.

A realm of reality is known in Romanized Sanskrit as dharmadhatu, which, according to the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “in Sanskrit, ‘dharma realm,’ viz., ‘realm of reality,’ or ‘dharma element.'”

Furthermore, “The Chinese Huayan School recognizes a set of four dharmadhatus (Chinese: 四法界).”

The Huayan School of Chinese Buddhism is also known as Huanyan Zong (Chinese: 華嚴宗). According to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Huayan Zong is “in Chinese, ‘Flower Garland School,’ an important exegetical tradition in East Asian Buddhism. Huayan takes its name from the Chinese tradition of the title of its central scripture, the Avatamaskasutra (or perhaps the Buddhaavatamsaka). The Huayan tradition is also sometimes referred to as the Xianshou zong, after the sobriquet, Xianshou (Chinese: 賢首法藏法師 ), one of its greatest exegetes.”

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra (Chinese=大方廣佛華嚴經/華嚴經), or The Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra (The Mahāvaipulya Sūtra named “Buddhāvataṃsaka”), is, according to this article, “one of the most influential Mahāyāna sutras of East Asian Buddhism.” “The text has been described by the translator Thomas Cleary as ‘the most grandiose, the most comprehensive, and the most beautifully arrayed of the Buddhist scriptures.’ The Buddhāvataṃsaka describes a cosmos of infinite realms upon realms filled with an immeasurable number of Buddhas. This sutra was especially influential in East Asian Buddhism. The vision expressed in this work was the foundation for the creation of the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which was characterized by a philosophy of interpenetration. The Huayan school is known as Hwaeom in Korea, Kegon in Japan, and Hoa Nghiêm in Vietnam. The sutra is also influential in Chan Buddhism.“

These four dharmadhatus are:

- The dharmadhatu of phenomena (Chinese: 事法界).

- “The dharmadhatu of the principle (Chinese: 理法界).

- “The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena (Chinese: 理事無礙法界).

- The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpretation of phenomena and phenomena (Chinese: 事事無礙法界).

From the names of these dharmadhatus, we can surmise that there are two realities in the four dhamadhatus: phenomena and principle.

While we can understand that phenomena refer to the myriad phenomena in the world, what is “principle (Chinese: 理)” that can be referred to as a “realm of reality.”

To understand that, we begin with the term tattva (Chinese: 實相), which, according to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “In Sanskrit, lit., ‘thatness,’ a term with two important denotations. First, it can mean ‘Ultimate Reality,‘ a synonym of Paramatha (English: Ultimate Truth, Chinese: 真諦) the reality, free from all conceptual elaborations, that must be understood in order to be liberated from rebirth, as well as the inexpressible reality that is the object of the Budaha’s omniscient consciousness. Second, the term may be translated as ‘principle.'”

Many Buddhist terms refer to the Ultimate Reality, each with a different perspective. “Principle (Chinese: 理)” is such a term for the Ultimate Reality from the standpoint that the Ultimate Reality is “free from all conceptual elaborations.” Indeed, as discussed in Post 4, Buddha uses “principle” to refer to the inconceivable realms of Citt and Rupa, and inconceivable means “beyond conceptualization.”

So, these four dharmadhatus concern different relationships between the visible phenomena of the world and the invisible mental world that is “free from conceptualizations,” i.e., Citta and non-liminosity.

A) The dharmadhatu of phenomena (Chinese: 事法界).

The dharmadhatu of phenomena refers to the visible phenomena of the world that humans experience.

B) The dharmadhatu of the principle (Chinese: 理法界).

The dharmadhatu of the principle refers to the world that is “free conceptual elaborations.” This dharmadhatu comprises the enlightened quiescent mentality of Citta (Chinese: 本覺心) and the dharmadhatu of the unenlightened fluctuating mentality of non-luminosity (Chinese: 無明), the two realms of reality in Buddha’s three-body cosmos.

C) The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena (Chinese: 理事無礙法界). We will try to interpret this dharmadhatu using Dr. Tong’s image below, which shows ripples as epiphenomena in a quantum energy field.

First, we interpret from the quantum-mechanical perspective, but in Buddhist terms. In the image, the epiphenomena represent the Buddhist dharmadhatu of phenomena. Since there is no “principle” in quantum mechanics, we will substitute it by calling it the dharmadhatu of quantum energy, or “quantitative properties.” So, in scientific terms, the dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between “principle” and phenomena means that epiphenomena of quantum energy and the mathematical equations that describe them are unobstructed.

Using the same image but from the Buddhist perspective and in Buddhist terms, the epiphenomena still represent the dharmadhatu of phenomena, but the dharmadhatu of principle becomes the fluctuating mentality in non-luminosity. However, since a fluctuating mentality is the definition of consciousness, these epiphenomena are conscious. So, the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena means that consciousness and epiphenomena are one. Humanity is a perfect example.

D) The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpretation of phenomenon and phenomenon (Chinese: 事事無礙法界).

Again, we can understand this dharmadhatu through Dr. Tong’s image. Again, the epiphenomena are the phenomena. The unobstructed interpretation of phenomenon and phenomenon means that all the epiphenomena are interconnected by the fluctuating field in which they are. Indeed, except for their difference over what connects the epiphenomena, the fact that epiphenomena are interconnected is another shared teaching between Buddhism and quantum mechanics.

Understanding the interconnectedness of all phenomena is critically important in Buddhism because it led the Buddha to teach humanity about altruism, compassion, empathy, and related qualities. Because all humans are connected, they are a community of equals. Being altruistic towards others should be a way of life for a community of equals, as it benefits both those who do good and those who receive the benefits. The primary difference between compassion and empathy is that compassionate deeds bring joy to others, whereas empathy alleviates sorrow in those who suffer.

(If you like this post, please like it on our Facebook page and share. Thank you.)

In this post, we discuss the Four Realms of Reality, a Buddhist doctrine in which the Buddha teaches that there are four ways of understanding reality between Citta and Rupa, the two realms of reality that comprise the Buddha’s three-body cosmos.

A realm of reality is known in Romanized Sanskrit as dharmadhatu, which, according to the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “in Sanskrit, ‘dharma realm,’ viz., ‘realm of reality,’ or ‘dharma element.'”

Furthermore, “The Chinese Huayan School recognizes a set of four dharmadhatus (Chinese: 四法界).”

The Huayan School of Chinese Buddhism is also known as Huanyan Zong (Chinese: 華嚴宗). According to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Huayan Zong is “in Chinese, ‘Flower Garland School,’ an important exegetical tradition in East Asian Buddhism. Huayan takes its name from the Chinese tradition of the title of its central scripture, the Avatamaskasutra (or perhaps the Buddhaavatamsaka). The Huayan tradition is also sometimes referred to as the Xianshou zong, after the sobriquet, Xianshou (Chinese: 賢首法藏法師 ), one of its greatest exegetes.”

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra (Chinese=大方廣佛華嚴經/華嚴經), or The Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra (The Mahāvaipulya Sūtra named “Buddhāvataṃsaka”), is, according to this article, “one of the most influential Mahāyāna sutras of East Asian Buddhism.” “The text has been described by the translator Thomas Cleary as ‘the most grandiose, the most comprehensive, and the most beautifully arrayed of the Buddhist scriptures.’ The Buddhāvataṃsaka describes a cosmos of infinite realms upon realms filled with an immeasurable number of Buddhas. This sutra was especially influential in East Asian Buddhism. The vision expressed in this work was the foundation for the creation of the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which was characterized by a philosophy of interpenetration. The Huayan school is known as Hwaeom in Korea, Kegon in Japan, and Hoa Nghiêm in Vietnam. The sutra is also influential in Chan Buddhism.“

These four dharmadhatus are:

- The dharmadhatu of phenomena (Chinese: 事法界).

- “The dharmadhatu of the principle (Chinese: 理法界).

- “The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena (Chinese: 理事無礙法界).

- The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpretation of phenomena and phenomena (Chinese: 事事無礙法界).

From the names of these dharmadhatus, we can surmise that there are two realities in the four dhamadhatus: phenomena and principle.

While we can understand that phenomena refer to the myriad phenomena in the world, what is “principle (Chinese: 理)” that can be referred to as a “realm of reality.”

To understand that, we begin with the term tattva (Chinese: 實相), which, according to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “In Sanskrit, lit., ‘thatness,’ a term with two important denotations. First, it can mean ‘Ultimate Reality,‘ a synonym of Paramatha (English: Ultimate Truth, Chinese: 真諦) the reality, free from all conceptual elaborations, that must be understood in order to be liberated from rebirth, as well as the inexpressible reality that is the object of the Budaha’s omniscient consciousness. Second, the term may be translated as ‘principle.'”

any Buddhist terms refer to the Ultimate Reality, each with a different perspective. “Principle (Chinese: 理)” is such a term for the Ultimate Reality from the standpoint that the Ultimate Reality is “free from all conceptual elaborations.” Indeed, as discussed in Post 4, Buddha uses “principle” to refer to the inconceivable realms of Citt and Rupa, and inconceivable means “beyond conceptualization.”

So, these four dharmadhatus concern different relationships between the visible phenomena of the world and the invisible mental world that is “free from conceptualizations,” i.e., Citta and non-liminosity.

A) The dharmadhatu of phenomena (Chinese: 事法界).

The dharmadhatu of phenomena refers to the visible phenomena of the world that humans experience.

B) The dharmadhatu of the principle (Chinese: 理法界).

The dharmadhatu of the principle refers to the world that is “free conceptual elaborations.” This dharmadhatu comprises the enlightened quiescent mentality of Citta (Chinese: 本覺心) and the unenlightened fluctuating mentality of non-luminosity (Chinese: 無明), the two realms of reality in Buddha’s three-body cosmos.

C) The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena (Chinese: 理事無礙法界). We will try to interpret this dharmadhatu using Dr. Tong’s image below, which shows ripples as epiphenomena in a quantum energy field.

First, we interpret from the quantum-mechanical perspective, but in Buddhist terms. In the image, the epiphenomena represent the Buddhist dharmadhatu of phenomena. Since there is no “principle” in quantum mechanics, we will substitute it by calling it the dharmadhatu of quantum energy, or “quantitative properties.” So, in scientific terms, the dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpenetration between “principle” and phenomena means that epiphenomena of quantum energy and the mathematical equations that describe them are unobstructed.

Using the same image but from the Buddhist perspective and in Buddhist terms, the epiphenomena still represent the dharmadhatu of phenomena, but the dharmadhatu of principle becomes the fluctuating mentality in non-luminosity. However, since a fluctuating mentality is the definition of consciousness, these epiphenomena are conscious. So, the unobstructed interpenetration between principle and phenomena means that consciousness and epiphenomena are one. Humanity is a perfect example.

D) The dharmadhatu of the unobstructed interpretation of phenomenon and phenomenon (Chinese: 事事無礙法界).

Again, we can understand this dharmadhatu through Dr. Tong’s image. Again, the epiphenomena are the phenomena. The unobstructed interpretation of phenomenon and phenomenon means that all the epiphenomena are interconnected by the fluctuating field in which they are. Indeed, except for their difference over what connects the epiphenomena, the fact that epiphenomena are interconnected is another shared teaching between Buddhism and quantum mechanics.

Understanding the interconnectedness of all phenomena is critically important in Buddhism because it led the Buddha to teach humanity about altruism, compassion, empathy, and related qualities. Because all humans are connected, they are a community of equals. Being altruistic towards others should be a way of life for a community of equals, as it benefits both those who do good and those who receive the benefits. The primary difference between compassion and empathy is that compassionate deeds bring joy to others, whereas empathy alleviates sorrow in those who suffer.

(If you like this post, please like it on our Facebook page and share. Thank you.)