After discussing how Buddhism and quantum mechanics meet in epiphenomena, we explore Buddhism’s complete list of “dusts” and compare it with how science arranges its list of particles according to the Atomic Theory, the Standard Model of Particles, and quantum mechanics.

Abhidharmakośakārikā (Chinese: 阿毗達磨俱舍論/俱舍論/), or Verses on the Treasury of Abhidharma, “is a key text on the Abhidharma written in Sanskrit by the Indian Buddhist scholar Vasubandhu (Chinese: 世親) in the 4th or 5th century CE.” “This text was widely respected and used by schools of Buddhism in India, Tibet, and East Asia. Over time, the Abhidharmakośa became the main source of Abhidharma and Sravakayana Buddhism for later Mahāyāna Buddhists.”

In the Abhidharmakośakārikā, a total of twelve “dusts” are mentioned, and an additional “dust” was mentioned in 佛學大辭典, or the Chinese Encyclopedia of Buddhism.

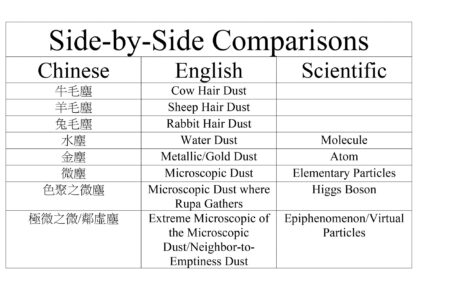

The “dusts” start with the coarsest “finger knuckle dust” and end with the tiniest” extreme microscopic of the microscopic dusts.” Out of the thirteen “dusts”, seven are selected for use in the side-by-side comparison table below. They are chosen either because they help explain the logic of how Buddha arranges his “dusts” or because they allow comparison with their corresponding scientific particles. The unselected ones do not serve either of these functions.

The two columns on the left are the Chinese names of the Buddha’s dusts and their corresponding English translations. Each of the rightmost columns lists particles or classifications of particles in science that correspond to those in the two left columns.

Now, let’s discuss them row by row.

1)The three dusts on top of the list are cow hair dust (Chinese: 牛毛塵), sheep hair dust (Chinese: 羊毛塵), and rabbit hair dust (Chinese: 兔毛塵).

They have no corresponding scientific particles. Instead, they are listed to help explain the logic of how Buddha’s dusts are arranged.

Imagine cutting the hair of cows, sheep, and rabbits in cross-sections. The area of the cross-section of the cow hair is larger than the area of the cross-section of the sheep hair and, therefore, can accommodate a larger dust. The same holds for moving from sheep hair dust to rabbit hair dust. The cross-section of the sheep hair is larger than the cross-section of the rabbit hair. In other words, Buddha arranges his “dusts” in descending order by size.

2) The next one from rabbit hair dust is water dust (Chinese: 水塵), and water corresponds to a molecule in science. By definition, a molecule “is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds.”

3) The next one after the water dust is gold dust (Chinese: 金塵). The Chinese character for gold, 金, can also signify any metallic particles in the Periodic Table. However, whether it is gold or another metallic element, it belongs to the category of atoms. Therefore, gold or metallic dust represents atoms. By definition, an atom “is a particle that consists of a nucleus of protons and neutrons surrounded by a cloud of electrons.”

4) The next smaller one after the gold dust is the “microscopic dust” (Chinese: 微塵). Smaller than atoms, “microscopic dust” corresponds to the Elementary particle group in the Standard Model of Particle Physics. By definition, an Elementary Particle (or fundamental particle) “is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles.”

According to the Standard Model of Particle Physics, there are seventeen elementary particles. However, among the seventeen elementary particles, there is a special one, listed separately from the others, as shown in the article linked above.

Known as the Higgs Boson, this special particle is named after Dr. Peter Higgs, who won a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013 for discovering it. The Higgs Boson distinguishes itself from the other sixteen elementary particles in the Standard Model because it “gives a rest mass to all massive elementary particles of the Standard Model, including the Higgs boson itself.”

So, what is mass?

In science, “mass was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a body until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementary particles, theoretically with the same amount of matter, have nonetheless different masses.”

Massive particles are essential in physics because constructing the universe is impossible without them. For this reason, the Higgs Boson is often referred to as the “God particle.”

The uniqueness of Buddha’s “microscopic dust” group is that, like the elementary particles in the Standard Model, it has a unique dust known as “microscopic dust where Rupa gathers (Chinese: 色聚之微塵).”

While the Buddha does not specify how many “microscopic dusts” there are in the group, it is certain that, from its name, “microscopic dust where rupa gathers” is a member of the “microscopic dust” group of “dusts.” By separating “microscopic dust where Rupa gathers” from the other members of the “microscopic dust” group, Buddha, like scientists, indicated that it is distinct from the rest of the group.

The uniqueness of the “microscopic dust where rupa gathers” can be understood from its name. Even though the “microscopic dust where Rupa gathers” is a member of the “microscopic dust” group, it is unique because it is “where Rupa gathers.”

As discussed in the post about Citta and Rupa, Rupa, according to The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, is “in Sanskrit and Pali, ‘body,’ ‘form,’ or ‘materiality,’ viz., that which has shape and is composed of matter.”

From their respective definitions, one can surmise that the key point to understand the relationship between “microscopic dust where Rupa gathers” and the Higgs Boson is that both contain matter. At the same time, they are also the first to do so in Buddhism and science, respectively.

Additionally, just as the scientific universe cannot be constructed without particles with mass, Buddha’s dependent originated universe also cannot be built without Rupa. It is because Rupa is the fourth link in Buddha’s doctrine known as the Twelvefold Chain of Dependent Origination. Indeed, being the early part of Buddha’s Twelvefold Chain of Dependent Origination, Buddha’s dependently originated universe cannot be built without Rupa. We will discuss this topic in the next post when we will cover namarupa.

7) The last and the smallest dust in Buddha’s list is known as “extreme-microscopic-of-the-microscopic dust (Chinese: 極微之微塵).” Also known as “neighbor-to-emptiness dust” (Chinese: 鄰虛塵), it was the tiniest epiphenomenon in the universe, and where Buddhism and quantum mechanics meet, as discussed previously. Therefore, it will not be discussed further here.

In science, three theories are necessary to compile the list of particles mentioned above: the atomic theory of atoms and molecules, the Standard Model of elementary particles, and quantum mechanics for epiphenomena. However, they all have deficiencies.

The atomic theory, which originated with the concept of atoms comprising a nucleus of protons and neutrons, with electrons orbiting it like mini solar systems, has long been abandoned. While the standard model of particle physics is widely accepted, it is considered incomplete because it does not explain gravity and therefore requires modification. Furthermore, as Dr. Harry Cliff, “a particle physicist at the University of Cambridge working on the LHCb experiment,” notes in his video lecture, “Beyond the Higgs: What’s Next for the LHC,” the theory leads to “a cold, dark, lifeless universe with a few photons whizzing through.” Similarly, quantum mechanics needs the Copenhagen Interpretation to give it meaning. While some scientists believe in using Wave Function Collapse to describe the Copenhagen Interpretation, others argue that the Copenhagen Interpretation requires consciousness to have meaning, believing that reality at its fundamental level is uncertain, fluid, and dependent on observation.“ That, of course, is also Buddha’s teaching. In Buddhism, the Five Aggregates, discussed in this post, is the doctrine that holds that observation makes reality visible.

In his investigation of nature, the Buddha did not need to make hypotheses, formulate theories, or conduct experiments. When he sat down at the Bodhi Tree to meditate until enlightenment, the only tool Buddha had was his conscious mind. By calming his mind to a state of “no thought,” the Buddha became enlightened. Enlightenment enabled the Buddha to perceive nature directly by becoming part of it. Perceiving nature directly enables Buddha to encompass “all objects of knowledge” that nature offers. By understanding “all objects of knowledge” of nature, Buddha did not need hypotheses, theories, or experimentations to investigate and understand nature.

No modifications were ever needed nor will they ever be required in Buddhism, because the Buddha’s understanding of nature is gained by perceiving it directly. If you ever doubted the ability of direct perception to understand the nature of reality, unless you think its contents are all coincidences, this post should not only alleviate some of that doubt, but also help you understand the power of direct perception to comprehend nature by enabling Buddha to be part of it. Furthermore, in Buddhist sutras, the Buddha teaches that the Buddhas of the past and future all teach the same thing, despite their teachings being separated by thousands of years, maybe much more. It is because they all teach about “What Exists?” in nature, which never changes.

(If you like this post, please like it on our Facebook page and share. Thank you.)